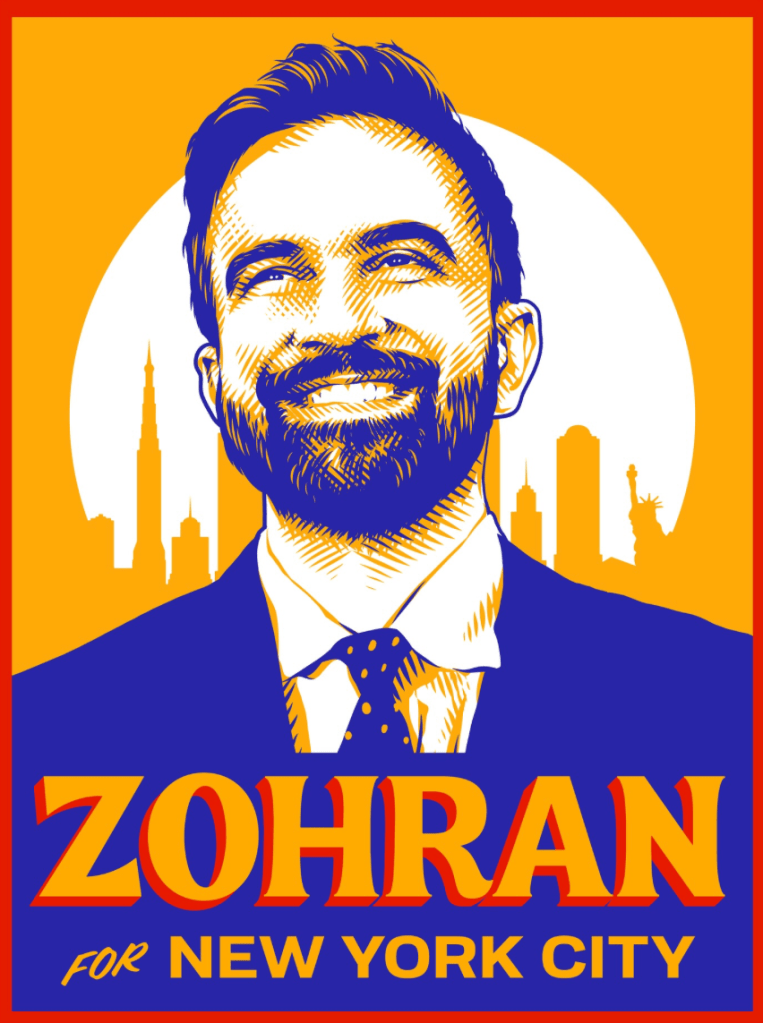

On a bitterly cold January morning, bustling with anticipation, poet Cornelius Eady stepped up to the inauguration podium for Mayor Zohran Kwame Mamdani. The city had gathered to mark a moment many once thought unimaginable: New York welcoming its first Muslim mayor of Indian descent, a young and, until recently, little-known assemblyman who had overturned an entrenched oligarchy and pulled off one of the most startling political upsets in the city’s history.

The cold looked almost symbolic. The air seemed sharp, the kind that stings the face and stiffens the hands, as though the weather itself were underscoring the improbability of the day. Eady sensed it too. Pausing, he joked that somewhere along the long road of the campaign, someone must have said, “Him? He’ll get elected… when hell freezes over.” Laughter rippled through the crowd, bright and immediate. It was the kind of laughter that warms you from the inside, the kind that reminds you that being together matters, especially when circumstances insist otherwise.

People stood bundled in coats and scarves, breath visible in the air, yet the mood carried an unmistakable warmth. Against the cold, there was closeness. Against disbelief, there was shared recognition. What had once seemed impossible had arrived, and the city had come out to witness it together. In that shared warmth, many felt the early signs of a different kind of political life beginning to take shape.

That sense of shared warmth did not end with the laughter or the applause but pointed toward a deeper shift people had been feeling, one that had been quietly building throughout the campaign and was now finding its public voice.

What many were responding to was a change in tone. Public life began to feel less armored, more open to care. People spoke about kindness without irony. They noticed an easing in conversation, a readiness to listen, a renewed capacity for generosity toward one another. Leadership, in this emerging vision, felt grounded in emotional presence as much as in policy, and politics began to feel like a space where human connection could breathe again.

That change in tone became most visible in moments that were small, unscripted, and deeply personal. During one of Zohran Mamdani’s public listening sessions, held without fanfare and away from the spotlight of the inauguration, a woman named Samina took her seat across from him.

Samina had moved to New York from Lahore, Pakistan. She held notes in her hands and began by apologizing for her English, speaking carefully and with intention. She told him she wanted to thank him for what she had been noticing since his election. Faces around her seemed gentler. Daily encounters felt less tense. She said his presence in public life had brought softness into people’s hearts during a time marked by strain and uncertainty. When Mamdani responded to her in Urdu and acknowledged her journey, he grew emotional. Tears gathered in his eyes as he listened. The exchange lasted only a few minutes, yet it carried the weight of recognition. Samina’s words named what many others had been sensing and struggling to articulate: that leadership can restore warmth to civic life simply by meeting people where they are.

Samina’s words lingered because they felt familiar in a deeper way. Her recognition of care in leadership echoed a longing that has surfaced across cultures and centuries. People have always noticed when those who hold power listen closely and allow their hearts to remain open. Long before modern elections and public offices, communities told stories to preserve the memory of such rulers.

In South Asian history and folklore, Razia Sultana endures as a ruler remembered for her visibility and openness. She appeared in public spaces, listened to grievances directly, and carried the responsibilities of rule with humility and resolve. Her leadership left an imprint because it remained close to the people it served. In Persian tradition, King Anushirvan lives on as a symbol of justice shaped by attention to ordinary lives. Stories recount how he walked among his people, listening to farmers and laborers, learning how policies touched daily survival. His authority grew from fairness and steadiness, and his name became shorthand for a reign grounded in care.

These figures appear again and again in cultural memory, sometimes through chronicles, sometimes through poetry and storytelling. Their presence reminds us that ethical leadership has always depended on proximity, listening, and a willingness to be shaped by the lives of others. When Samina spoke, she gave voice to this same understanding. She recognized a quality of care that societies have long held up as worthy of remembrance, one that continues to reappear whenever power is exercised with human attention.

These rulers remain present in memory because their stories were carried forward, told and retold in homes, courts, and marketplaces. Over time, ethical leadership took on narrative form, becoming part of the shared imagination. This is how figures like Anushirvan and Razia Sultana moved beyond their own eras and entered a wider cultural vocabulary about care and responsibility.

That same vocabulary appears vividly in The Thousand and One Nights. In its stories, rulers leave the safety of their palaces and walk through their cities, listening to the lives unfolding around them. They hear grievances in kitchens and courtyards. They learn how policies ripple through households and livelihoods. Wisdom grows through attention. Justice follows from closeness. These tales endure because they offer a clear insight: societies change when power stays near the people, when leadership remains porous to human experience.

Seen this way, Samina’s encounter feels part of a much longer story. Her words echo the same recognition that animated these narratives centuries ago. She sensed care where others might overlook it. She named softness as a civic force. In doing so, she reminded us that leadership grounded in listening has always been one of the ways trust is restored and collective life renewed.

This lineage helps explain why Mamdani’s example resonates beyond one city. When people witness leadership shaped by attention and humility, it unsettles long-held assumptions about authority. It invites comparison. It raises expectations. Across borders and political systems, people recognize the familiar contours of ethical rule when it appears. They measure their own leaders against it. In this way, one example begins to travel, quietly but insistently, carried by shared human memory.

That sense of continuity, of memory carried forward, was articulated in Cornelius Eady’s poem on that cold January morning. The poem felt like an offering made into a shared space, shaped by the same attention and care that had drawn people there. Eady’s words reached for those whose lives are so often pushed to the edges of public life and brought them into the centre of the moment.

He asked questions that many of us have carried quietly for years:

Who said you were too dark? Too large, too queer, too loud? Who said you were too poor, too strange, too fat? You have to imagine it. Who said you must keep quiet? Who heard your story then rolled their eyes? Who tried to change your name to invisible?

The poem, aptly entitled Proof, held these questions without rushing to answer them. It allowed recognition to settle in the body. Standing together in the cold, people felt themselves named and seen. The words gathered those who have been dismissed, corrected, overlooked, or erased, and placed them squarely within the civic story of the city. In that act of gathering, softness became visible as a form of strength. Care took on public shape.

This was the same moral lineage traced through stories of rulers who listened closely and governed with humility. It was present in the laughter that rose when Eady spoke of frozen hells and improbable victories. It lived in the simple fact of people showing up for one another on a freezing day.

That is the proof. Proof that shared attention can restore warmth to public life. Proof that leadership shaped by care can bring people together across difference. Proof that softness, long pushed aside, has found its way back to power.

Written by Merlin Ince