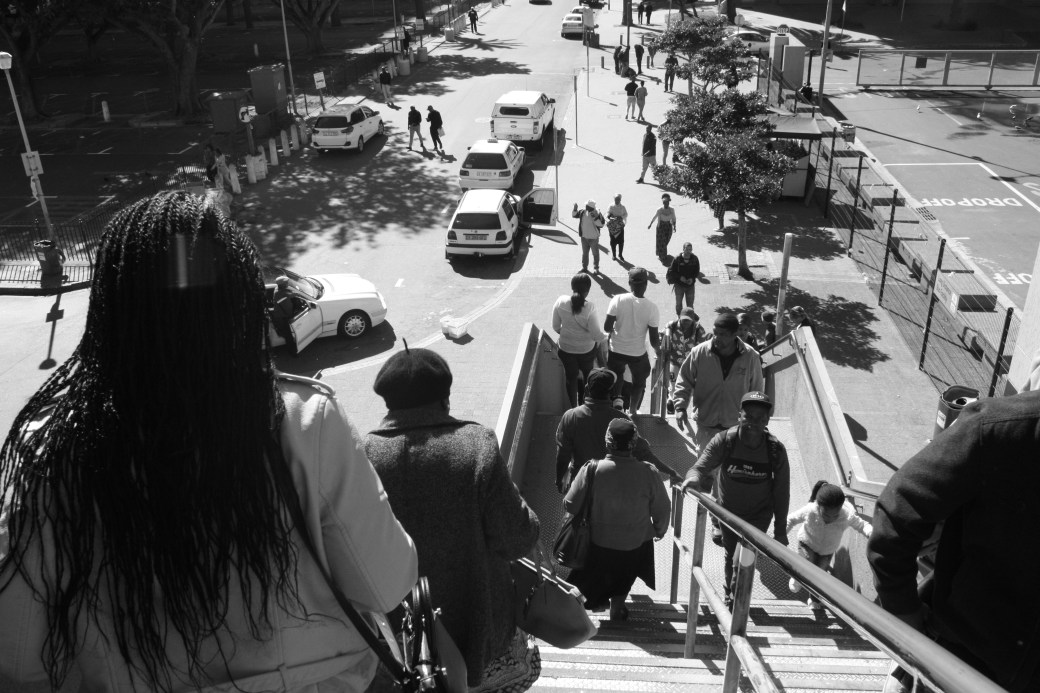

Young men in Manenberg, Cape Town, doing informal vehicle repair work to earn a living

No one ever chooses to live in a ghetto, and the chances of overcoming the structures that keep people there are few. Like many poor neighbourhoods on the Cape Flats in South Africa, ghettos were designed as spaces to contain and segregate people of colour. Uprooted from prime property identified for lucrative development opportunities of the apartheid government, black and coloured people were structurally excluded through the euphamised concept of ‘separate development’. Today, more than two decades since this legislation was dismantled, promises of an open and free society still elude ghetto neighbourhoods. These marginal spaces continue to be ignored like the surrounding highways that direct traffic to distant economic hubs.

Looking for work under such confined circumstances is a shadowed and grim reality that is often lost on the mainstream. Youth like Natheem, who grew up in the historically segregated neighbourhood of Manenberg on the Cape Flats, relate poignant stories of the daily hustle to find work. Along with a group of his friends, who live in the same block, they wash windows and carpets. They perform shopping errands for house-bound residents, and use their combined skills to do household repairs or to fix appliances.

For Natheem, it conveys an almost desperate sense of needing to provide for each day, of having to think about how he will get his next meal, how units can be purchased to feed the electricity meter, how fundamental needs such as cooking and cleaning can be managed: “The most I get is maybe ZAR50 for washing all the windows, kitchen, room, sitting room and maybe make two carpets clean or I also do upholstery like chairs are broken, then I get new material and then I fill that pieces [using] my own imagination. I do that because I won’t give up…if I’m gonna give up then there is nothing.”

Like many other youth growing up in ghetto neighbourhoods, the prospects of Natheem finding a permanent job are slim. He dropped out of school at the end of Grade 9 despite being an exemplary learner who was even selected as Head Prefect at his primary school in Grade 7.

His family was largely supported by his parents who also made a living from irregular domestic work and gardening, but his family suffered great tragedy. Natheem’s mother died of a heart-attack and within two years of her death, his father was caught in the crossfire shootout between police and gangs in the neighbourhood. He died from his injuries. With only Natheem’s older brother providing a meagre income through contract construction work, Natheem felt obliged to leave school and look for work.

Inasmuch as poverty and personal tragedy are common life experiences in neglected neighbourhoods, structural impediments impose further challenges that youth encounter on their education and employment pathways.

According to Statistics South Africa 2011, high school completion rates are as low as 12% among the adult population in ghetto neighbourhoods such as Manenberg, giving way to little motivation and cultural capital to finish school Unemployment rates are as high as 47% of the total workforce, meaning that youth are in contact with a limited number of people who can provide job referrals and information about job opportunities. These limited social networks confine youth to work role models who cannot inspire them to persevere at school, study further, and pursue professional careers.

At a community meeting in Hanover Park, another historically segregated neighbourhood on the Cape Flats, a high school teacher shared his thoughts on the schooling experiences of learners. The curriculum prescribed by the National Department of Education favours teaching models of small classroom numbers where teachers pay close attention to individual learner needs. There is also a large part of the syllabus that requires homework to be closely supervised by adults. But with classroom numbers averaging between 40 to 50, teachers struggle to keep every learner up to speed. At home where most households are run by single parents, adults have barely enough time to take care of chores and are burdened by the adversities of trying to make a living with little resources available.

Many youth fall through the cracks, with weak foundations in their early education that cannot cope with the incremental pace of studies in higher grades. In many ghetto neighbourhood schools, poor resources result in teachers spending more time on administrative tasks and less time teaching, sometimes as little as 46% of a 35-hour week (Sayed & Motala, 2012:112), leading to learner outcomes that are far below the national standard. Most drop out in Grade 9, at a rate of about 78% (Statistics South Africa, 2011). Their employment expectations are minimal, explains the teacher whom I interviewed: “They don’t think further than what they see. They don’t think doctor, professor, scientist, astronaut. They are happy with getting a job at the local supermarket or hustling on the streets because that is the only thing they know.”

Without a high school certificate, the opportunities for full-time work are very scarce. The demand for labour, through deindustrialisation, has shifted economic focus away from the manufacturing industry towards employment in industries such as tourism, information technology, film, and finance. Jobs that do not require a high school certificate, namely semi-skilled manual jobs, even unskilled manual jobs, have grown slower than jobs that require a high school certificate or even a tertiary education qualification.

Economic sociologists such as Borel-Saladin and Crankshaw (2009: 653) highlight job trends in Cape Town that show a decline in manual work employment for the manufacturing industry, while increases are noted for managerial, technical, and professional jobs as well as middle-skilled clerical, retail and sales jobs.

Excluded from mainstream economic trends, youth in ghetto neighbourhoods become disillusioned and vulnerable. Rose, a 22-year-old single mother in Manenberg, dropped out of school after she failed her Grade 9 examinations. She shared with me her experience of being recruited by an insurance company to conduct door-to-door policy sales. For each policy of ZAR300 that she sold, she received ZAR30 commission. The recruitment process did not require an interview or presentation of a CV. It offered little training and only supported workers with transport to and from areas in which they were required to conduct sales. Rose was often hungry and tired. She was not well versed in the terms of the policy and struggled to explain it to me when I probed the subject during our interview. She sold two policies in the space of ten days and then quit out of sheer exhaustion and frustration.

Her experience of exploitation is also evidenced in her hairdressing services to women in her neighbourhood following a training course that Rose completed at the local community development centre. She would accept to do a job for ZAR10 that would ordinarily cost ZAR100 at a hair salon and often not get paid, with women promising to pay her at the end of the month and then not honouring their commitments.

Without close, consistent, and concentrated intervention, youth in ghetto neighbourhoods face bleak futures in terms of their employability. This intervention needs to begin at the level of basic education, building learner confidence through after-school mentoring programmes. The isolation that youth experience must be counteracted through exposure to career guidance and the cultural capital that empowers them to navigate opportunities such as student financial aid schemes. If they are left to the demise of social structures that prevent them from competing for jobs in high demand, they will always struggle to transform their circumstances.

Without interventions that are designed acknowledge, affirm and develop inherent skill, their experience of work will remain a daily hustle and grind for underpaying and irregular jobs. And for this our society is all the poorer without Nobel laureates, global leaders, and innovators whose talent was ignored and relegated as a marginal identity.

Written by Merlin Ince

References:

1. Borel-Saladin J & Crankshaw O (2009) ‘Social polarization or professionalization? Another look at theory and evidence on deindustrialization and the rise of the service sector.’ Urban Studies 46(3): 645-664.

2. Sayed Y & Motala S (2012) ‘Getting in and staying there: Exclusion and inclusion in South African schools’. Southern African Review of Education 18(2): 105-118.

3. Statistics South Africa (2015) Census 2011: Income dynamics and poverty status of households in South Africa. Pretoria.

Photograph Credit: Lu Nteya