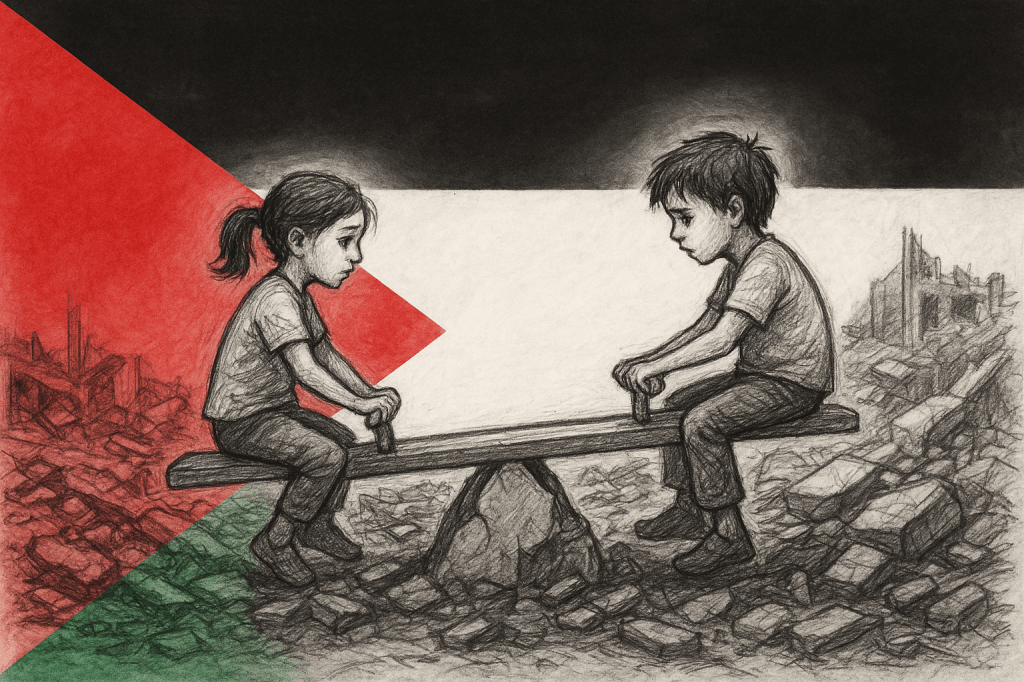

We have all been watching Palestine for decades. We have witnessed the blockade by Israel, the bombings, the rubble. We have seen the images of children deliberately targeted and killed, children with bandaged limbs, children pulling siblings from collapsed buildings, children writing in notebooks beside the ruins of their homes. And yet, it is only now, after tens of thousands have been killed, that some in the international community have begun to name this horror for what it is: a genocide.

Why must children bear the burden of our hesitation? Why do we wait so long to call evil by its name? Have we not learnt from history that, in every genocide, children pay the heaviest price?

In Southern Africa, during the 17th and 18th centuries, the genocide of the Khoi and San people began with the displacement of children. Severed from their ancestral lands, taken into servitude and forced to abandon their identity, their erasure ensued relentlessly by colonial powers[1]. With the Herero and Nama people, in the early 1900s, children were deliberately starved and denied medical care in concentration camps[2]. During the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, more than 300,000 children were killed, and an estimated 95,000 were orphaned in just 100 days. Thousands more were forced into armed groups, carrying weapons instead of schoolbooks, their childhoods stripped away in the violence[3]. Children were also systematically marked and targeted during the holocaust, with more than 1.5 million killed. Those who survived often endured medical experiments or brutal labor, their innocence erased as part of a calculated extermination[4].

In every case, children were not merely accidental victims of violence. They were deliberately targeted because they carry the possibility of a people’s survival. To erase children is to erase the future.

This same pattern has been unmistakably visible in Palestine. At least half of Gaza’s population are children, yet they have been among the most systematically killed and maimed by Israeli forces. Schools, playgrounds, and hospitals, as spaces meant to shelter the young, have been bombed repeatedly[5]. Countless children have been killed, with more buried under rubble or dying slowly from hunger and untreated injuries. Tens of thousands more are now orphans. This deliberate targeting of children in Gaza is not new, but the scale and sheer brutality is unprecedented.

We ought to recognize by now that the targeting of children is always the first and clearest sign of genocide.

In 1948 the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was passed[6], promising “never again.” The convention, while powerful on paper, is however tragically inadequate in practice. It defines genocide legally but is not proactive. It responds after catastrophe, rather than preventing it. It also relies on states to enforce action, but political alliances and veto powers silence urgent intervention. One of the greatest weaknesses is that the convention does not compel response at the first warning signs. The deaths of children become proof of genocide rather than a trigger to stop it. By the time the world officially speaks the word “genocide,” it is already too late for the children buried in shallow graves.

Beyond those who are mercilessly killed, survival is not free of pain. We know very well the trauma of violence that stubbornly lingers well beyond childhood. Studies have consistently shown that trauma carried in childhood shapes generations. These are the ‘living genocides’, the slow, invisible killing of potential, joy, and hope. A girl who grows up without parents, without safety, without security, does not simply “heal” when the bombs stop. A boy who watches his family killed will carry that scar into adulthood, into parenthood, into the raising of the next generation.

Genocide is not only about the killing of bodies. It is about the killing of futures.

If we are indeed committed to “never again,” then the protection of children must be the red line we refuse to cross. What would it mean to rewrite our conventions with children at the center?

- Early-warning triggers: If children are being targeted, displaced, or denied food, water, or medication, this should automatically initiate international investigations and interventions.

- Mandatory protections: Bombing schools and hospitals should immediately trigger accountability mechanisms, without waiting for political approval.

- Humanitarian corridors: Guaranteed, enforced pathways for children and families to access food, water, and medical care, even and especially against state objections.

- Accountability: Leaders who order or enable the harming of children must face international justice swiftly, not decades later.

- Denouncing hate speech: As a known precursor to genocide, dehumanizing rhetoric should be addressed through punitive action against those using and spreading derogatory terms about specific population groups.

Perhaps the Genocide Convention already contains these principles in theory, but in practice, it has been ineffective. The world does not need more words. We need proactive legislation that protect children before their futures are destroyed.

Genocides expose the worst of humanity, not only in the cruelty of perpetrators but also in the apathy of bystanders. To remain silent while children are killed is not neutrality; it is complicity. To abstain from naming genocide is to allow it to continue.

Children should not have to carry the weight of our hesitation. We must act when it matters most. For the sake of our children, we can never hesitate to call evil by its name and confront it with all the courage humanity owes its future.

Written by Merlin Ince

[1] Adhikari, Mohamed. The Anatomy of a South African Genocide: The Extermination of the Cape San Peoples. Ohio University Press, 2011.

[2] Olusoga, David & Erichsen, Casper W. The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism. Faber & Faber, 2010.

[3] Human Rights Watch, Rwanda: Child Soldiers, 2003.

[4] United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), “Children During the Holocaust.

[5] UN OCHA, Occupied Palestinian Territory: Hostilities in Gaza, situation reports, 2023–2024.

[6] UN Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect, The Genocide Convention.